Tony Warren

Well-Known Member

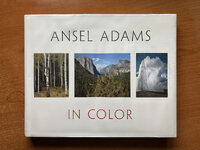

I have just finished re-reading a book you may not have heard of called “Ansel Adams in Color” (ISBN:0-8212-1980-4) that I came across some time ago.

Adams and monochrome are inseparable but it transpires he shot around 3000 colour images and was retained by Kodak in the development and use of Kodachrome from the 1930s onward and, later, by Polaroid including work on Polacolor. His colour work was almost entirely confined to commissioned professional work and reading about it brought out the huge conflict he had with the medium. Reading his writings he found it almost impossible to come to terms with the completely different practice and aesthetic compared to mono. His musical training and his need to completely control his monochrome medium in the way necessary for a piano recital must have influenced his reactions greatly.

Most interestingly, despite his reservations, he saw colour as the future and effectively foresaw digital in his comments on electronic imaging as he called it. The book really brings out his dilemma. He only felt really satisfied working in monochrome whilst becoming involved with colour processes payed the bills. At one point some sheet film Kodachromes for Kodak helped pay for film to tackle the Guggenheim fellowship he received.

Yet, despite all that, in 1969 he said “…were I starting again, I am sure I would be deeply concerned with color. The medium will create its own esthetic, its own standards of craft and application. The artist, in the end, always controls the medium”.

The book finely describes the contrast between photgraphy as it matured in the late 20th century, strongly influenced by commercial outcomes, and the dedicated, almost obsessive approach that the photographer had had to take previously.

Adams and monochrome are inseparable but it transpires he shot around 3000 colour images and was retained by Kodak in the development and use of Kodachrome from the 1930s onward and, later, by Polaroid including work on Polacolor. His colour work was almost entirely confined to commissioned professional work and reading about it brought out the huge conflict he had with the medium. Reading his writings he found it almost impossible to come to terms with the completely different practice and aesthetic compared to mono. His musical training and his need to completely control his monochrome medium in the way necessary for a piano recital must have influenced his reactions greatly.

Most interestingly, despite his reservations, he saw colour as the future and effectively foresaw digital in his comments on electronic imaging as he called it. The book really brings out his dilemma. He only felt really satisfied working in monochrome whilst becoming involved with colour processes payed the bills. At one point some sheet film Kodachromes for Kodak helped pay for film to tackle the Guggenheim fellowship he received.

Yet, despite all that, in 1969 he said “…were I starting again, I am sure I would be deeply concerned with color. The medium will create its own esthetic, its own standards of craft and application. The artist, in the end, always controls the medium”.

The book finely describes the contrast between photgraphy as it matured in the late 20th century, strongly influenced by commercial outcomes, and the dedicated, almost obsessive approach that the photographer had had to take previously.